|

| A chance to see some of my favourite people and study one of my favourite things! |

I'm beginning the conference on Wednesday by demonstrating virtual reality to teachers from across the province at Brenda Sherry and Peter Skillen's Minds on Media. MoM (or in this case MEGA MoM) is a showcase of #edtech in action, and a must see event. As an emerging technology VR is going to have a profound influence on education in the future. Having a chance to give people a taste of that future is exciting. The only reason I've been able to explore VR as it emerges is because of the DIY lab I'm presenting on Friday.

I get to spend the Thursday soaking up the latest in technology and how it can amplify pedagogy. On Friday I'm presenting on why you should develop your own do it yourself school computer lab and how to do it.

I first presented the concept at ECOO four years ago. It's taken me that long to develop the contacts and build a program that can do the idea justice. I've always felt that offering students turn-key no-responsibility educational technology was a disservice, now I'm able to demonstrate the benefits of a student-built computer technology lab and explain the process of putting one together. I realize I'm swimming upstream from the put-a-Chromebook-in-every-hand current school of thought, but that's my way.

The other major change was that my department got reintegrated into technology (it was formerly a computer science based mini-department of its own). Back in tech I was suddenly able to access specialist high skills major funding and support and found I was able to build the DIY concept - something I could never have done without our board's tech-support funding model.

Thanks to that new, adaptive, open concept IT approach I'm able to access a BYOD wireless network with anything I want. I don't have to teach students on locked down, board

imaged, out of date PCs. My computer engineering seniors helped me build what we now have and the results have been impressive. In addition to students in our little rural school suddenly winning Skills Ontario for information technology and networking, we're also top ten in electronics and, best of all, the number of students we have successfully getting into high demand, high-tech post secondary programs is steadily rising.

When I thought it might be interesting for students to get their hands on emerging virtual reality hardware in the spring it was only a matter of finding the funding. We built the PC we needed to make it happen and then it did. We've had VR running in the lab for almost half a year now at a time when most people haven't even tried it. Because we were doing it ourselves, what costs $5000 for people who need a turn key system cost us three thousand. We're now producing those systems for other schools in our board.

When I thought it might be interesting for students to get their hands on emerging virtual reality hardware in the spring it was only a matter of finding the funding. We built the PC we needed to make it happen and then it did. We've had VR running in the lab for almost half a year now at a time when most people haven't even tried it. Because we were doing it ourselves, what costs $5000 for people who need a turn key system cost us three thousand. We're now producing those systems for other schools in our board.A do it yourself lab is more work but it allows your students and you, the teacher, to author your own technology use. Until you've done it you can't imagine how enabling this is. My students don't complain about computers not working, they diagnose and repair them. My students don't wonder what it's like to run the latest software, they do it. Does everything work perfectly all the time? Of course not, but we are the ones who decide what to build and what software to use to get a job done, which allows us to understand not only what's on stage but everything behind the curtains too.

If that grabs you as an interesting way to run a classroom, I'm presenting at 2pm on Friday. If not, fear not, ECOO has hundreds of other presentations happening on everything from how to use Minecraft in your classroom to deep pedagogical talks on how to create a culture that effectively integrates technology into education.

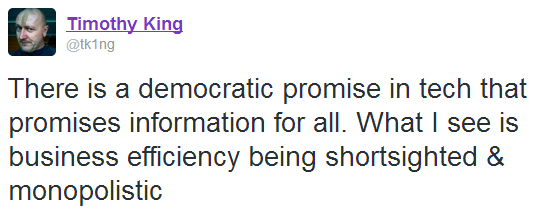

If that grabs you as an interesting way to run a classroom, I'm presenting at 2pm on Friday. If not, fear not, ECOO has hundreds of other presentations happening on everything from how to use Minecraft in your classroom to deep pedagogical talks on how to create a culture that effectively integrates technology into education. Thursday's keynote is Shelly Sanchez Terrell, a tech orientated teacher/author who offers a challenging look at how to tackle technology use in education. Friday's keynote is the Jesse Brown (who I'm really looking forward to hearing), a software engineer and futurist who asks tough questions about just how disruptive technology may be to Canadian society.

If you're at all interested in technology use in learning, you should get down to Niagara Falls this week and have a taste of ECOO. You'll leave full of ideas and feel empowered and optimistic enough to try them. You'll also find that you suddenly have a PLN of tech savvy people who can help, enable and encourage your exploration. I hope I can be one of them.

If you can't make it, you can always watch it trend on Twitter:

#bit16 Tweets

note: to make a feed embed on twitter, go to settings-widget-create new and play with it, very easy!