If I hear this one more time I might pop. We're no busier than we ever were. If we were all so busy we'd have solved world hunger, the impending energy crisis, unemployment, racism, our broken democracies and poverty. If we're all so terribly busy, what is it that we're busy with, because it doesn't appear to be anything important.

If I hear this one more time I might pop. We're no busier than we ever were. If we were all so busy we'd have solved world hunger, the impending energy crisis, unemployment, racism, our broken democracies and poverty. If we're all so terribly busy, what is it that we're busy with, because it doesn't appear to be anything important.Most recently I heard it on CBC radio when someone was talking about an online dating site that allows you to quickly, with little more than a photo and a couple of bio points, select a date and meet them. Not surprisingly, the CBC piece was on the disasters that have come from this. When asked why people do it, the interviewee trotted out, "well, we're all just so busy now-a-days." I would suggest that if you are too busy to develop a considered relationship with a possible life partner, then you're getting what you deserve.

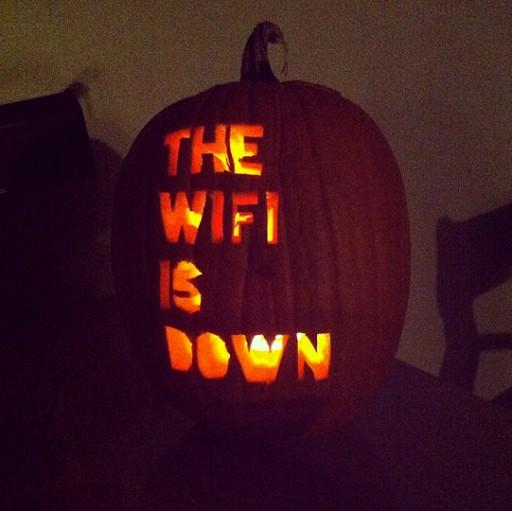

| These people aren't busy, they are distracted. |

There are those who are leveraging social media in interesting ways, but for the vast majority it is a passive time sink that has conditioned them to do many things poorly and barely ever finish a thought.

This myopia feeds data bankers who make a lot of money from the freely given marketing information. It also feeds the industry that creates a treadmill of devices to cater to the process. Lastly, our digital myopia also feeds the egos of all the 'very busy' people who see themselves as a vital part of this wonderful new democracy.

At yoga the other week our instructor gave us this: pain is inevitable, suffering is optional. There are things we need to do in life in order to survive and thrive: look after our bodies, look after our minds, look after our dependants, seek and expand our limitations, find a good life. This can be very challenging, but it is dictated by choice. When we make good choices we tend to see a reward. Eat well and feel better, expand your mind and learn something new, look after your family and enjoy a loving, safe environment. Poor choices lead to poor circumstances. In a world where we have more dependable machines and efficient communication, we should enjoy a sense of ease greater than previous generations who had to tune carburetors and ring through telephone exchanges.

Make some good choices. How busy are you really?