A conversation a colleague tole me about a while back:

Teacher to student: "You look pensive"

Student: "No, I'm just thinking..."

***

Before the break we were discussing reflective reading practices in a senior English class.

Students had a real hate on for journal writing while reading. The argument, when it wasn't that it was too much work, was that it wasn't reflective but merely make-work.

Even when journal writing was on the table I had to keep emphasizing that there was to be NO retelling of the story (I've read far to many poorly retold stories and they aren't reflective). With journal writing off the table, I asked for suggestions and got none whatsoever.

So, students didn't want to do the standard journal writing assignment for reflecting on their ISU reading, but they didn't have any other ideas either. I took a moment and threw out some ideas on our class online discussion board:

- a prezi mind-map of the story looking at plot/narrative, character, themes, setting and how they interact in the novel over time (a timeline of plot with other idea structures interacting with it might prove interesting and instructive)

- a series of key moment symbolic representations of the novel, graphic in nature with short written explanations of specific elements in the images and how they relate to the novel

- a film adaptation pitch, complete with actor, costume, set and prop suggestions linked to specifics (quotes) in the novel.

- author biographical research review: based on author research, an 4-6 paragraph explanation of how the author's background plays into specifics in the novel

- non-journal, but reflective reading notes from when you read the novel (can't be done after the fact). If you have an extensive set of notes based on the novel as you read it, these might work.

- Script (or scripted video) of an interview with the author (you have to play the author if you're videoing it), speculation on themes you're curious about based on your close reading of the novel.

Even with this many suggestions (and open to others) the class felt that reflecting on their ISU novels was something being done to them. Unfortunately reflection doesn't work very well as a forced exercise.

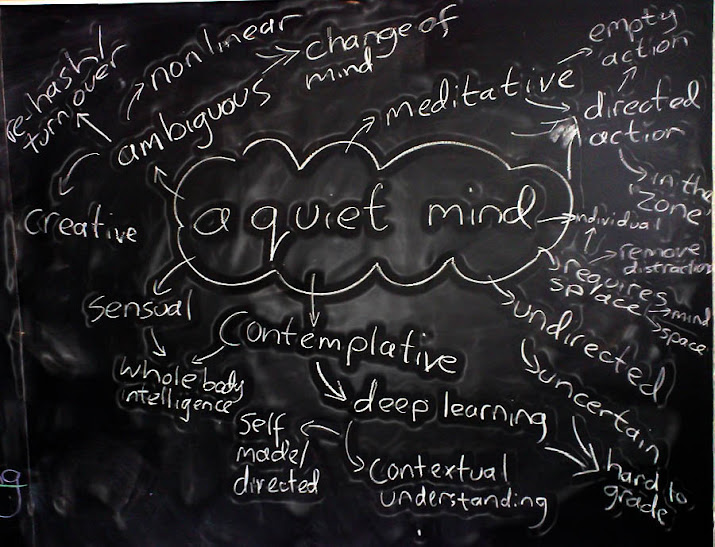

What followed was a brainstorming session about what a meditative, reflective mind looks like:

|

| Yes, I photoboarded that :p |

Students found the ideas behind the discussion foreign. School was something done at them; idea transmission, skill development, habits and bells. The goals behind reflecting on reading assume many things that most students simply don't do in school because schools aren't designed for that kind of thinking.

Meditative response relies on deep reading. Only an uninterrupted, contemplative reading of a text can get you to a reflective, contextual, personal response. The hacknied, piece-meal approach to reading that the majority of students undertook (because the assigned reading was 'done' to them, and they are in a state of constant digital distraction anyway) precludes reflection.

Even the idea of reflection was foreign. Students kept asking for clarification on exactly what it was they were supposed to be doing. What specifically should they write about? Can they offer opinion? Do they have to quote the text? What they were digging for was an 'A-B-C', 'this then that' set of instructions. Something easily gradable and fill in the blankable - exactly what school has taught them to expect from learning.

Meditative reading, reflective response, and deep study in general is a dying art. Artists create using it, scientists invent using it, but students seldom come close to it in school. Standardization kills it, digitization simplifies it and the marks hungry university bound English student is less interested in developing a quiet, meditative mind that offers deeply connective thinking than they are in keeping it simple, direct and easily achievable.

Post note:

While in teacher's college I had a senior English student, desperate to squeeze marks out of an assignment begging me for details on his Hamlet grade. He'd done a good job analyzing the text, though he had made a couple of errors in his explanations of quotes, and didn't always demonstrate consistent knowledge of the narrative. He begged for a higher grade than his 93%. I told him about the errors, but he wanted more grades anyway, so I asked him a harder question: "Years from now you'll be able to go to Stratford and immerse yourself in a piece of Shakespeare and really enjoy it. Isn't that a wonderful thought? So many people will never get it, but you do, and your understanding will only deepen over the years. It's exceptional now, and I don't doubt it will get better. Do you really need more numbers on this paper?"

Turns out he didn't.