I did a research piece for Canadian School Libraries last winter that looked at how you might develop the complex, multi-disciplinary digital skills you find in cybersecurity in a relatively short period of time. When I first put it together I found myself spending a lot of the time at the front of the paper trying to define the digital skills we find ourselves lacking. I came to the conclusion that adopting high abstraction digital tools such as those you find in cyber, A.I. and other emerging technologies makes for an impossible leap when we don't have the basics in place.

How we've missed this in education is a good question. Anyone with a background in the field knows that there is no such thing as a 'digital native' and that this myth, which has caused so much damage as it prevents education from building meaningful digital pedagogy, kicked off what has become a multi-generational skills shortage that is doing real damage to both the economy and students' future prospects.

Digital technology has worked its way into everything in 2025, so being unable to make productive use of it damages our ability to compete in a digitally connected world. That we continue to hum and haw about what digital fluency is and how to build it suggests that we're not going to resolve this problem any time soon in Canadian classrooms.

We've seen coding and computational thinking finally worm their way into education curriculums, but this is the tip of a much bigger iceberg when it comes to understanding what digital skills are and how we should approach them.

|

| Originally created for this post on why education is seemingly unwilling to address a persistent digital skills shortage (from 2023). |

I've been pushing the boundary of what constitutes digital skills ever since I first got knocked out of digital technology by the compsci grads who had claimed the keys to the kingdom. It took me decades to recover and come around to the approach I have now that nurtures my hacking mindset rather than dismissing it.

That siloing is also hobbling digital literacy development. The current coding/computational thinking fixation is just the latest in a long line of compsci blinkered approaches to addressing digital technology literacy. What would it look like if we represented the true breadth of digital and taught that wider scope of understanding in our classrooms? We use this technology daily to do everything from operate our schools to deliver learning across all subjects, but then avoid teaching how it all works at all costs.

At the Moonshot event I was introduced to the CEO of MineConnect, an organization that represents and works to promote the mining industry in Ontario. Our chat at Moonshot led to introductions with Science North over their Mine Evolution game. I'm hoping to get a web based version of that running on UBC's Quantum Arcade - perhaps with a quantum add-on as quantum sensing is going to drastically improve s in how we mine in the next decade.

What does this have to do with digital literacy? The fact that you're asking this question shows how little most people understand about where digital technologies come from, and that understanding should be a part of their literacy, don't you think? If you look up 'digital supply chain' you don't get what we need to build digital technologies, instead you only information on how to 'go digital'. Even industry goes out of its way to ignore what digital technology is... except in rare mineral mining, hence my work with Mine Connect and Science North.

It's incredible to me that this late in our adoption of this technology that we still go out of our way not to teach what is needed to make digital happen. The current wholesale adoption of A.I. in education is a great example of this ignorance, as was the rush to the cloud. There is no cloud (it's someone else's computer) and A.I. isn't intelligent, but we'll grasp at digital straws with willful ignorance if we think it'll make our lives easier.

In the CSL research I created a pyramid that showed how I taught digital awareness from the ground up in my rural high school. The assumption is that 'kids nowadays' know all of this, but that simply isn't the case. If you want to disable a 'digital native' it's as easy as flipping a switch they don't usually use. If you want to send a room of them into a panic unplug the Wi-Fi router (assuming you know what that is and where to find it).

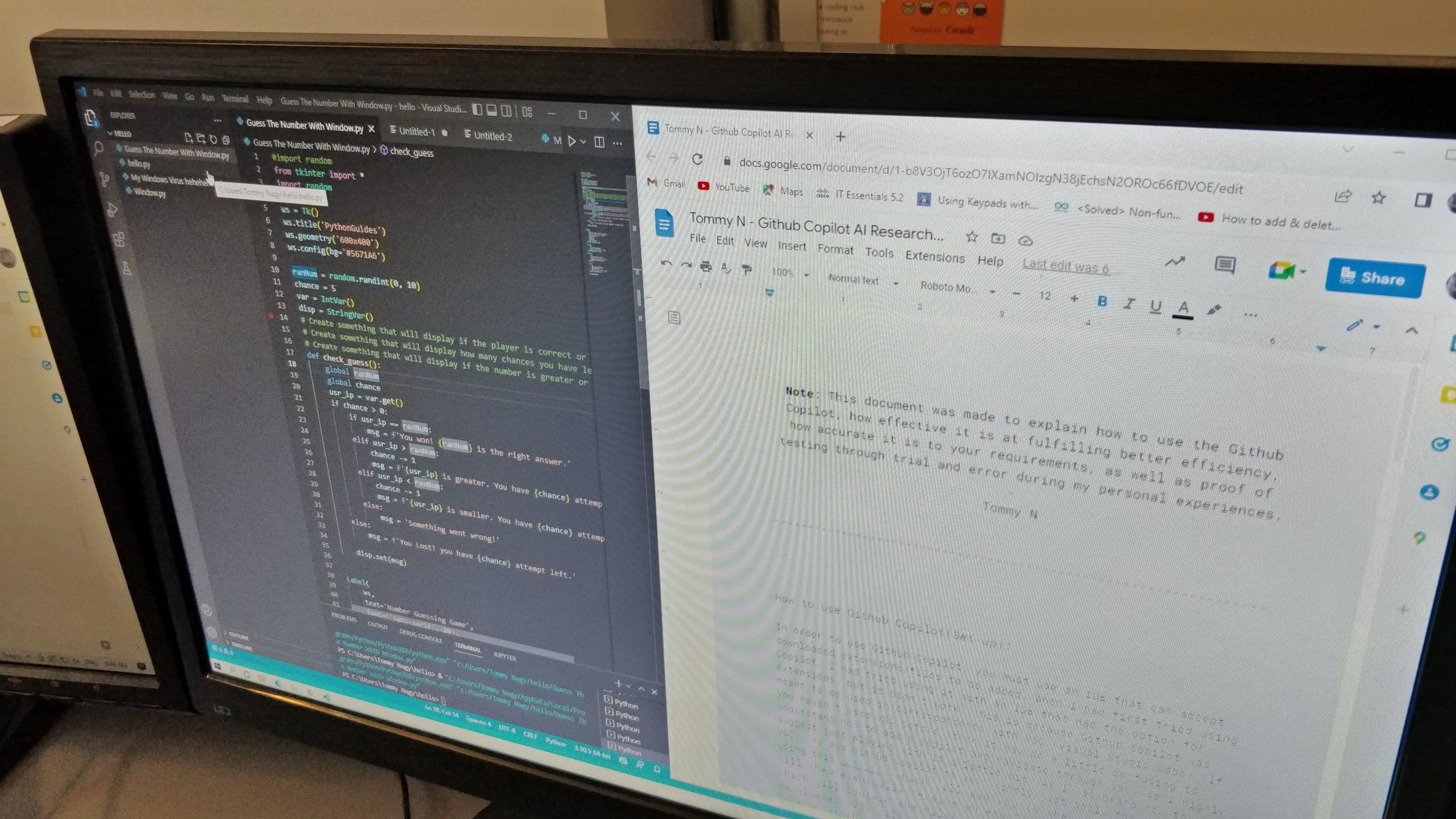

|

| Start with the physical substrata and work your way up into the more abstract realms of digital technology; starting digital fluency at coding is like starting literacy at poetry. |

In grade 9 I got a lot of digitally engrossed students who thought they knew it all because adults who lack even basic digital familiarity have been telling them that for years. Revealing that this perceived expertise is merely familiarity with a couple of devices and specific software doesn't take long. In many cases these kids had owned a series of game consoles and phones and that's it. Familiarity with software is limited to games and social media. Very few knew what an operating system was let alone the firmware that kick start it; this is literally how all computers work yet almost no one seems to know it.

Last week I was in Ottawa doing an introduction to OSes on our cyber range. The grade 5s didn't know what an OS was, but by the end of our 90 minutes they certainly did. They also learned the boot process any digital device goes through from firmware start-up to OS loading to where most users think computers start - when the desktop appears. They also got to interact with Linux as well as Windows on their Chromebooks (we use a cloud based cyber range so you're not limited to the restrictive OS on your local device). None of the students knew what Linux was, but they use it everyday because their Chromebook ChromeOS is Linux based. By the end of our afternoon they were navigating the settings in multiple OSes and understood how you could interrupt boot sequences to gain control and interrupt processes.

That we hand students tools like these without any understanding of what they are or how they work is a great failure in modern education, especially as we are only accelerating our use of these machines in classrooms. Considering how widespread their use is now, digital skills have become an ignored foundational literacy.

***

How did I tackle this ever widening digital divide in my program? We started by making our lab DIY. My seniors and I built the first iteration out of e-waste and then kept improving it as we found resources. In 2015 I returned tens of thousands of dollars in board run desktops which then got converted into half a dozen chromebook carts for other classes to use. In that first year our DIY conversion saved the board over tens of thousands of dollars.

In 2016 I contacted AMD and asked if they'd provide CPUs for our next upgrade, and they did! Our board's SHSM program provided additional funding and for a fraction of the cost of a board run computer lab we had significantly better hardware and control over installing our own OSes and software, which allowed us to provide digital learning opportunities others couldn't reach.

By 2018 we had a mix of AMD APUs that could handle the graphic modelling we were doing in our game-dev class. This meant they were also more than capable of running any other software we needed to build digital fluency from scratch. In the process my one teacher department went on to win multiple national awards across a staggering range of digital domains ranging from coding and electronics to IT & Networking, 3d modelling and cybersecurity. DIYing is essential if we're to build digital skills without those compsci coding blinkers on. Even worse is buying a ready-made 'edtech solution' which does it all for you and doesn't teach anyone (staff or students) how technology works. It also tends to trap you in a single brand rather than striving for agnostic digital comprehension.

Having a flexible digital learning environment that we built ourselves allowed us to create unique student projects. In grade 9 that means starting with Arduino micro-controllers. Not only did these open source electronics allow us to develop an understanding of the circuits that all digital technologies depend on, it also offered a tangible approach to programming where the lines of code would produce direct outputs like turning on lights or making music. By the end of the Arduino unit students were confident in building circuits and for many it was also their first opportunity to code in text as opposed to blocks.As you can see by the gif, getting into Arduino in grade 9 means that by grade 10 students are building customized electronics solutions to everything from the PC temperature system you see to various robotics and digital art installations. One of my seniors worked out an Arduino based fuel management system for his pickup that he then sold to others. Understanding the electronics substrata that digital operates in is imperative for well rounded digital literacy.

From that basis in electronics and introductory coding we moved to information technology and networking - two subjects studiously ignored in schools even though every one of them depends on both to operate every day. We begin I.T. by walking students through PC parts in our recently delivered Computers For Schools desktops. After covering the safety requirements for tools and working with machines that can contain enough electricity to knock you out if you don't treat them with respect, we dug in.The biggest point I make in PC building is about static management. As long as students respect the delicacy of the electronics (which they already understand thanks to Arduino), they quickly gain confidence and are never again tyrannized by this technology. After this unit no one calls a desktop PC a "CPU", because that's just one part of a much bigger device. Calling a desktop a CPU is like calling a car an engine.

We typically spend a week taking a part desktops and putting them back together. Getting them is no problem because no one wants desktops these days and CFS has piles of them they're aching to give to classrooms. When we wrap up the IT unit anyone who wants to take their computer home can - you'd be surprised how many students (and teachers) don't own a home computer. The best part? If it ever goes wrong they know how to fix it because the built it from the hardware up.

Once we got the hardware figured out we installed operating systems. This involves interrupting boot processes and learning how to navigate BIOSes and other types of firmware. Everyone gets to the point where they have Windows and Linux installed, but some students want to build an epic stack. This can involve adding extra hard drives and going through install processes on up to a dozen OSes. By the end of week two we've got OSes installed and students have explored many more than the one that came on their phone or game system (which are often Linux based). We've even had our share of Hackintoshes in the lab.Our final step in the IT/Networking unit is to connect the desktops together on a local network and figure out IP addressing and all those other connectivity details most people have no concept of even though they use them daily. Building a network like this takes it out of theory and into tangible practice, as does the PC building. By the end of the week no one is calling connectivity 'WIFI' any more. Ethernet is ethernet and wireless is wireless and everyone knows how to configure and troubleshoot both. The motivation is that once we've got our network up and running on a domain where everyone can see each other we cue up a LAN party and everyone plays networked games on their DIY systems.

We do eventually get to coding of course, but starting that far up the tech pyramid is absurd. High level coding languages (the only ones schools teach) are resource heavy because they spell out commands in easy to understand English (easier for humans = harder for machines). We did HTML and associated languages in grade 9 so the internet didn't baffle anyone anymore. In grade 10 it was Python simply because it's in such wide use. In the senior grades students choose their own coding focus, but not before I drag them through an introduction to low level 'machine language' programming so they have an appreciation for all the work those high level languages are doing for them. After you've had to do your own memory addressing, it changes you.

Leveraging this digital literacy, my seniors helped keep the tech in our building running smoothly. This not only saved money but also gave students invaluable public facing support experience. Perhaps the best example of this was our Chromebook graveyard. We would take in broken machines and then repair them with bits from others. After a couple of years of service most high schools in our board had lost over a quarter of their Chromebooks to abuse and accidents - we enjoyed a 90%+ active rate meaning more computers for more students at no extra cost.

The 'that's not your job' thinking that most boards operate under prevents this kind of innovation and cost savings. I always am left wondering to whose benefit.

The other benefit was that our digital fluency made us resilient. When COVID struck and everyone else folded up their classes and went home early, the digitally fluent students in my program didn't want to lose their semester's work and we went online, created our own Discord and landed it remotely. It took a bit of re-culturing because the students needed reminding that this isn't a gaming Discord - you're at school, but they quickly adapted and were sharing 3d models, Unity code snippets, circuit designs and network details back and forth to build complex demonstrations of their skills. In many cases they were doing it on the PCs they'd built when they were in grades 9 or 10 because many parents thinking digital technology is a toy.

So what's stopping us from graduating digitally fluent students with a wide range of skills who are ready to go into any field they choose because every one of them these days involves some kind of digital technology? I come from a time when home computers were brand new and no one had worked out how to 'do them' yet. In that primordial binary goo I hacked my own software and learned how to build my own hardware. My millwright apprenticeship turned to IT because of my familiarity with this new technology but I never came at it as a scientist might, but rather as a mechanic would. Hacking isn't bad, it's humans finding ways to approach digital technology as agents rather than consumers.

If we're going to tackle complex interdisciplinary digital technologies like artificial intelligence with anything other than willful ignorance, we need to start building an understanding of digital from the ground up so students and teachers can see beyond the box tech companies want to keep you in. If we're putting children on it, we should be showing them how it works so that they become more than what most of us are: consumers.

|

| This is from a decade ago. FB has faded from relevance, but every 'tech' we use follows the same approach: your attention is the product being sold. |

It might sound counter-intuitive, but cybersecurity offers a unique approach to tech that other subjects lack. Cyber is inherently about edge cases and encourages a 'meta' mindset when approaching digital environments. You're not a component inside the system, you've recognized its limitations and are working beyond it where being human is not only a benefit but essential. With all the 'AI doing it for you' going on these days does being human matter? Other approaches seem easier and wear 'academic credibility' better, but what is academic credibility but another system meant to contain your thinking? If we keep our current status quo we will, at best, produce another generation of passive consumers. We've tried that and it isn't going well. Time to hack this problem by putting students back in control of the technology we are using to control them. It's time to embrace your inner hacker.