There is a strong undercurrent of animosity about what teachers get paid and a lot of misinformation about teacher average pay. Like anything, it's more complicated than it appears. Here's my stab at trying to explain how Ontario teacher pay works, though the people complaining about it probably aren't interested in any facts:

The latest Ontario secondary teacher salary grid from my board:

To get your foot in the door on this grid you need to have spent 4 years in an undergraduate degree and then another 2 years getting your bachelor of education. If you've ever had any trouble with the law you're already out of contention. You need to have a clean criminal record to be a teacher.

Your average cost for a university degree in Canada these days is about $6500 a year.

So you’re about $40,000 in debt before you even get a whiff of that ‘super’ teacher pay. Ontario is (of course) one of the most expensive places in Canada to get your post-secondary education:

So that $6500 Canadian average turns into almost $8000 a year and your Ontario teacher is typically sitting under about fifty grand in debt to get onto the grid.

Six contract sections don’t exist for new teachers these days. From what I've seen, you’d be hard pressed to find any Ontario teacher under 30 years old who has six contract sections (full time equivalence - six sections is a full year of work). It’s fair to expect most teachers to take 5-6 years to get to full contract these days, many give up on the process. There are a number of teachers who, for various reasons, never get to six contract sections and are part time throughout their career.

Remember that salary grid? To get up the sharp end of it you need to have an honours degree in what you’re teaching and then take additional qualification (AQ) courses after teaching experience to earn your ‘honours specialist’ and get into the top ‘level 4’ section of the salary grid.

A number of teachers never get there because they don’t have the university background or aren’t willing or able to spend thousands more dollars when they aren’t teaching to get additional qualifications. You can look up any teacher on OCT to see what their qualifications are and whether they’ve spent more of their own time and money to get additional qualifications: https://www.oct.ca/Home/FindATeacher

So, to get up to the top end of the teacher’s salary, currently $96,068 in my board, you need to have dropped at least fifty grand on university degrees plus another couple of thousand on honours specialist additional qualifications. Most teachers don’t stop there and get other AQs in other specializations as well (I have 2 other subjects I've AQ'd in as well as my honours specialist).

Because of all these variables, calculating what the actual average teacher salary is in Ontario is a tricky business, which is why no one has bothered, but I'll give it a go:

Your first year you're teaching as an occassional teacher at the bottom of the grid. Let's be wildly optimistic and say you're teaching six sections (full time) on a short term contract, but many aren't. From years 2-6 let's say you're getting one contract section a year and are still able to fill up the rest of your time table with short term contract jobs (again, many aren't). Let's assume you've got an honours degree in what you're teaching. In your third year you drop another couple of thousand bucks on getting your honours specialist and move up to level four on the salary grid and keep climbing year over year.

That eighty-three grand average is mighty optimistic. It ignores the endemic under-employment in new teachers these days. It also ignores maternity leaves and any other family or medical leaves that happen in people's lives as well as the fact that a sizable portion of teachers never get to that level four on the grid. I'd estimate that the average Ontario teacher is making something more like seventy grand a year, with many making substantially less.

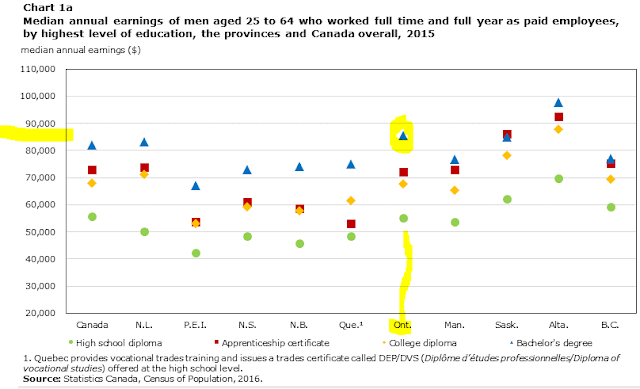

Wild eyed conservative leaning reporters will bleat on and on about how the average Ontarian should rise up against these overpaid teachers, but when you look into statistics around pay and education level, the typical degree carrying Ontarian makes about $85,000 a year. Your average teacher salary is significantly less than that:

Playing that rhetorical game and equating people who have spent years of their lives and tens of thousand so their own dollars to earn a qualification with people who haven't is a nasty bit of neo-con politics. The people playing that game are trying to sell you on equality when they're actually selling the opposite. We live in a society that rewards dilligence, competence and effort, don't we? We want our dentists to be able to fix teeth, our mechanics fix cars and our teachers teach our children the skills they need to survive in an increasingly competitive world facing some very big challenges. Professionalism matters, doesn't it? Maybe it doesn't in our new, blue, Ontario.

The benefits and pension piece are another angle that gets a lot of air play. I pay almost eight hundred bucks a month into my pension. If everyone paid that much into a pension plan, they too would have a good one waiting for them. The only difference between teachers and everyone else is that we're forced to do it. My take home pay as a teacher only equalled my take home pay as a millwright from 1991 in 2015, after eleven years in the classroom and tens of thousands of dollars spent on training and qualifications. I'll have a better pension when I retire as a teacher than I would have as a millwright (though National Grocer's millwrights were well looked after until they broke the union and fired them all in the late '90s).

There is another side to these conservative attacks on teaching that often goes unnoticed. I'm always left with the vague feeling that there is some good old fashioned sexism implicit in the politics levelled against educators. Almost 70% of teachers in Canada are women, and there is no glass ceiling in it because we're paid equally for the work we do. I imagine this grates on the nerves of the manly conservative men who are looking for reasons to hate on the job and the unions that enabled this equity, but I gotta tell ya, most of those dudes wouldn't last five minutes in a classroom.

If you're able to handle the crushing student debt, the hatred of people who couldn't or wouldn't do what it takes to do the same job and have the resiliency to survive in classrooms (stats show that typically about 30% of people who do the degree work drop out of teaching), then teaching is a rewarding profession, and one of the few remaining that let you lead a middle class life.

If you're able to handle the crushing student debt, the hatred of people who couldn't or wouldn't do what it takes to do the same job and have the resiliency to survive in classrooms (stats show that typically about 30% of people who do the degree work drop out of teaching), then teaching is a rewarding profession, and one of the few remaining that let you lead a middle class life.

|

I just spent most of the day making no money and walking the picket lines

for better learning conditions for my students while we all struggle under

an almost psychotically vindictive provincial government who seem intent

on hurting the most vulnerable students in our system. |

Some stats to consider:

There has been a lot of mis-information around Ontario teachers making the highest salary in Canada. That’s not true either: www.narcity.com/life/these-are-the-highest-and-lowest-paying-canadian-cities-for-teachers

Toronto is 4th out of 8 on this 2018 list. Teachers get paid more in Nunavut, Alberta and Manitoba, and only make a couple of grand more than teachers in Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan. I’m sure you can quickly figure out the difference in housing costs between Toronto and Halifax or Toronto and Saskatchewan…

|

| Canada is close to the world average in terms of education spending as a percentage of government spending. Again, Ontario is the largest single system in the country, so we wag that dog too, but expect to be attacked for it. |

|

| In terms of cost we're pretty much neck and neck with the USA, but Canada is top 10 in the world, the US isn't in the top 30. If you want to be acknowledged and rewarded for a job well done don't teach in Ontario. |

What Finland is really doing to improve its acclaimed schools:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/08/30/what-finland-is-really-doing-improve-its-acclaimed-schools/

"We have learned a lot about why some education systems — such as Alberta, Ontario, Japan and Finland — perform better year after year than others in terms of quality and equity of student outcomes. We also understand now better why some other education systems — for example, England, Australia, the United States and Sweden — have not been able to improve their school systems regardless of politicians’ promises, large-scale reforms and truckloads of money spent on haphazard efforts to change schools during the past two decades.

Among these important lessons are:

- Education systems and schools shouldn’t be managed like business corporations where tough competition, measurement-based accountability and performance-determined pay are common principles. Instead, successful education systems rely on collaboration, trust, and collegial responsibility in and between schools.

- The teaching profession shouldn’t be perceived as a technical, temporary craft that anyone with a little guidance can do. Successful education systems rely on continuous professionalization of teaching and school leadership that requires advanced academic education, solid scientific and practical knowledge, and continuous on-the-job training.

- The quality of education shouldn’t be judged by the level of literacy and numeracy test scores alone. Successful education systems are designed to emphasize whole-child development, equity of education outcomes, well being, and arts, music, drama and physical education as important elements of curriculum."

Still want to earn that easy teacher money? Jump on in, the water's tepid.