If you're in education you're probably still teaching 'the' industrial revolution. Our subjects are still siloed and scheduled that way. There is little different in school organization and planning from how an early 20th Century office operated... and we're still focused on producing graduates for that non-existent office. It's probably just a habit. Public education was formed in the first industrial revolution and copied many of the forms from that time. What's frustrating is that these systems are unable or unwilling to change now.

An early 20th Century office - you don't have

to think too hard to see what classrooms

were modelled on. Teaching tech in one

isn't any fun, especially when you're

buried in massive classes.

When I became a technology teacher I quickly learned that there is 'hard' tech and 'soft' tech. I found those descriptions amusing because the hard techs often had low expectations and my 'soft' techs had more demanding expectations, to the point where my principal told me I had to make them easier. I preferred using traditional tech and future tech, which turns out is how most of the world sees them.

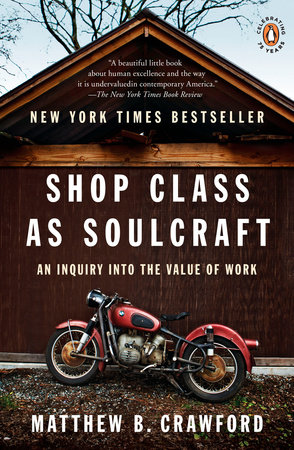

In traditional tech you're doing wood and metal working and auto mechanics following Industry 2.0 processes (hands on fabrication). Having come from millwrighting and spending a significant proportion of my free time working on mechanics, I have a love of working in these traditional skills, but if we're aiming students at skilled trades we're decades out of date.

|

| Yep, there are four industrial revolutions, and most of the world is at about 3.2 on their way to 4.0. In education we're still rocking Industry 2.0 in most tech classes. |

There are inherent dangers with traditional techs. Industrial machines can cut and burn you if you aren't careful, especially if you're going to teach these skills in an Industry 2.0 hands-on way. As a result, these classes are capped at 21 students and often run with significantly fewer. My 'soft' tech classes, even though we were operating soldering irons and power tools and working with live electricity that could kill, were capped at 31 and ran in a classroom rather than a dedicated technology space. The icing on the cake was when, during COVID scheduling, all my colleagues went home at lunch to ignore eLearning in the afternoon (because you can't teach 'real' tech like that) while I was teaching my second cohort of students in-class while simultaneously juggling eLearning because there were no other qualified teachers to do it. This might sound like a lot of moaning but it demonstrates in a systematic way how education is mis-labelling in-demand skills and unevenly distributing limited resources to teach what is actually needed. It turns out what we were covering in 'soft' tech has more to do with manufacturing than most of what was happening in 'hard' tech classes.

The rest of the world has already experienced three industrial revolutions and is now deeply immersed in an emerging forth one. If you're going to be teaching skilled trade technologies you need to be focusing on robotics and IT automated systems, and that's if you're aiming at the last Industry 3.0 targets. If you're aiming to make students ready for the world of work they're going to enter, you should be teaching machine learning, IoT (internet of things - ie: smart devices with networked sensors) and even AI (also things we cover in computer technology, except it's all applicable to manufacturing).

The nomenclature matters because it's used to direct funding. The current government in Ontario is very focused on skilled trades, which is a good thing because our academically run education system isn't kind to non-academic students, but the definitions it operates with aren't accurate. My son just started working at the factory around the corner. They're in an Industry 3.0 strance with non-machine learning (programmed) robots doing repetitive work (including welding which is still taught by hand in manufacturing classes like it's 1960). They need humans to do the in-between work, but the new factory going in next door will be fully automated and will leverage Industry 4.0 to the point where there will be few manual labourers but many more IT and robotics technicians (if they can find them) along with a plethora of support services such as cybersecurity and cloud services to make this highly efficient process hum.

Guess where all those manufacturing job skills are happening? In poorly resourced/treated as a second thought computer technology classes. Ontario needs to wake up and revise its technology curriculums to align with the technology students will be expected to know when they leave the make-believe world of education.

I was talking to the dad of a former student a couple of weeks ago. His son got into robotics in my program about 5 years ago. He graduated, went to college for a robotics technician qualification and has never been unemployed since. He currently works for Toyota Canada and is being sent down to the States to learn the new welding processes their robots will use. Those are the same robots my son is working with around the corner. This is pretty thrilling for me as a teacher from a manufacturing pipeline perspective. I have a former student coding the robots that recent grads are using in their work... in manufacturing.

%20(1).png)